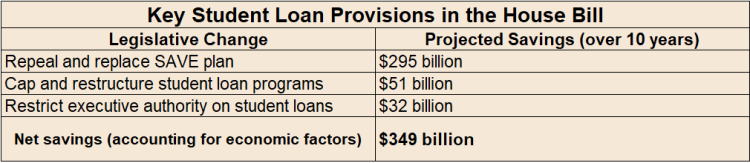

On May 22nd, the House of Representatives passed a budget reconciliation bill, known as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA). While much of the public focus has centered on tax cuts and reductions to entitlement programs like Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the legislation also contains far-reaching changes to higher education policy. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected $349 billion in net savings from reforms to federal student loans and grant programs. In tandem with a series of executive orders issued by the Trump administration to reverse President Biden’s student debt policies, the reforms represent a significant shift in the federal government’s approach to higher education finance.

Replacing and Reforming Repayment Plans

At the heart of the House’s education provisions is the repeal of President Biden’s Saving on a Valuable Education (SAVE) Plan—an income-driven repayment (IDR) program that lowered monthly payments and accelerated forgiveness for millions of borrowers. CBO estimates that repealing SAVE will account for $295 billion of the proposed higher education savings. The House bill introduces a replacement IDR program called the Repayment Assistance Plan, alongside a more traditional standard repayment plan.

A standard repayment plan requires borrowers to make fixed monthly payments—calculated based on the total loan balance—over a 10-year period (or up to 30 years for consolidated loans). This is the default repayment plan for federal student loans and is designed to pay off loans quickly, though it can be more financially burdensome for lower-income borrowers due to higher monthly payments compared to IDR plans. An IDR plan uses a borrower’s income, and occasionally other identifying factors like family size, to set monthly repayment rates.

The House bill’s proposed Repayment Assistance Plan would:

- Require a minimum monthly payment of $10, regardless of income

- Set repayment rates between 1% and 10% of gross income

- Provide a $50 per month reduction in required payments for each dependent child

- Offer a principal match of up to $50 per month for qualifying borrowers, a feature the SAVE plan did not have

- Forgive remaining balances only after 30 years of repayment

In contrast, the now-halted SAVE plan required borrowers to pay only 5–10% of discretionary income above 225% of the federal poverty line, with monthly payments as low as $0 for low-income borrowers. Forgiveness occurred as early as 10 years into repayment for certain borrowers, but ranged up to 25 years depending on loan type and repayment history.

The SAVE plan was implemented via executive action, prompting legal challenges from multiple states over the administration’s authority to make such sweeping changes without Congressional approval. In 2024, a federal court issued an injunction halting SAVE and placing borrowers on the plan in forbearance, pending the outcome of these lawsuits.

To manage the transition, the House bill outlines a transitional repayment plan based on 15% of discretionary income, with forgiveness after 20–25 years. Borrowers could remain on this plan or opt into the new repayment options.

Curtailing Borrowing and Increasing Accountability

Beyond repayment plans, the OBBBA proposes tighter controls on borrowing:

- Undergraduate loans would be capped based on the average cost of a student’s academic program

- Graduate loans, previously uncapped, would now face limits

- Interest would accrue during enrollment, eliminating the current in-school subsidy

Together, these measures are expected to save $51 billion over a decade.

The legislation also introduces a “risk-sharing” model for institutions: colleges with poor loan repayment outcomes among graduates would be required to repay a portion of federal loans issued to their students. The recovered funds would be redirected toward federal grant support for high-performing, low-cost institutions.

Additional reforms include:

- Stricter Pell Grant eligibility, based on income, part-time enrollment status, and citizenship.

- A $10 billion investment over three years to address a projected Pell Grant funding shortfall that has resulted from significantly increased enrollment in the program and larger award sizes.

Limiting Executive Authority

A third major prong of the bill aims to rein in executive control over student loan policy. New statutory limits would prevent future administrations from:

- Forgiving student debt via executive order

- Unilaterally modifying repayment terms without Congressional approval

The bill tasks the Secretary of Education with ensuring that any regulatory changes to loan programs do not increase the federal government’s financial liabilities. These provisions are projected to generate $32 billion in savings over 10 years.

Executive Actions from the Trump Administration

In parallel with legislative efforts, the Trump administration has issued several executive orders that reverse existing federal loan policies. On May 5th, 2025, President Trump resumed federal student loan collections, ending the COVID-19 repayment pause that had been in place since March 2020.

Another order restricts eligibility for the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program, which expanded dramatically under President Biden from around 7,000 approvals before 2022 to over 1 million by early 2025. The new executive order excludes organizations deemed to have a “substantial illegal purpose” from PSLF participation – a move likely to face legal scrutiny.

Looking Ahead: What the Senate Will Consider

As the reconciliation process moves forward, substantial changes to education and loan programs will be on the table to meet both the reconciliation instruction goals and the Trump administration’s education policy priorities.

Continue Reading