Budget Gimmicks Mask True Cost and Erode Faith in Institutions

Now that the House has passed its reconciliation bill – the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) – that increases the Federal debt by around $3 trillion over ten years, attention shifts to the Senate as they take up the bill. Unfortunately, the Senate’s reconciliation instructions include only $4 billion in deficit reduction and would allow a ten-year increase in the debt of over $5 trillion. Despite these differences, House and Senate budget proposals are similar in that they both make excessive use of budget gimmicks that mask the true cost of the budget proposals. These budget gimmicks both exacerbate fiscal problems and undermine the public’s faith in Congress as responsible stewards of the public’s finances.

Jessica Riedl of the Manhattan Institute, and recent guest on Concord’s Facing the Future podcast, outlined the 10 worst federal budget gimmicks in a recent article in Reason Magazine. The OBBBA includes several of these gimmicks, discussed in more detail below, that mask the true cost of the proposal, provide political cover for Congress to make irresponsible fiscal choices, and erode the confidence of both citizens and financial markets in the ability of Congress to craft fiscally responsible policy.

Unrealistic Economic Assumptions

One of the on-going debates about tax cuts is whether and how much they will “pay for themselves” by increasing economic growth and therefore increasing federal tax revenues (referred to as dynamic effects or dynamic scoring). Most economists believe that tax cuts do stimulate some economic growth, but the revenues generated almost never even come close to covering the full cost of the tax cuts. Additionally, deficit financed tax cuts increase the debt and related interest payments which in turn creates a negative economic effect that may offset the benefits of tax cuts.

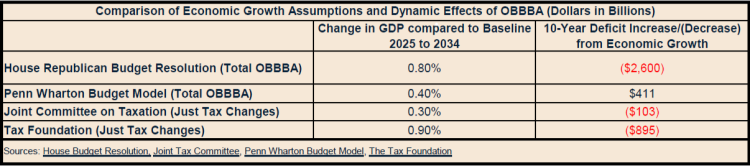

By gaming the economic growth assumptions, policymakers can make deficits seem to disappear. The House budget plan uses rosy economic scenarios to support claims that the legislation will not add around $3 trillion to the national debt over ten years – as estimated by the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. The budget resolution anticipates that aggressive economic growth will generate additional tax revenues of $2.6 trillion, partially offsetting the deficit increase. The House budget plan assumes a growth rate of 2.6 percent in real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) compared to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) baseline growth of 1.8 percent (or 0.8 percentage points greater). In an analysis released after OBBBA passed, the Penn Wharton Budget Lab estimated the economic impact of the entire bill and found a 0.4 percent increase in GDP but despite the growth, the analysis finds that the bill will actually decrease revenues rather than cause them to grow and therefore increase the debt by $411 billion over ten years. This unexpected decline in revenues is driven by policy changes in the bill that will create incentives for workers to work less rather than more.

Focusing just on the tax portion, the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) found that between 2025 and 2034 the plan would increase real GDP by 0.3 percent compared to the baseline, far less than the House Republican assumption. This increase in economic growth would generate additional revenue of $103 billion to offset the ten-year debt increase of around $3 trillion, according to JCT. The Tax Foundation, in an analysis of just the tax provisions, found a 0.9 percent increase in GDP and ten year debt reduction of $895 billion. As such, even the most optimistic forecast of economic growth from outside analysts finds that the House Republican plan would increase the deficit by more than $2 trillion.

The Fallacy of the “Current Policy Baseline”

The Congressional Budget Office uses a “current law baseline” to project future government finances. This means that if a law is set to expire, the projections assume it will no longer exist after its end date. Any tax or spending changes are measured against this baseline to estimate their impact on deficits and the debt. However, the Senate budget plan uses a concept known as the “current policy baseline” to mask the total cost of the budget plan. A current policy baseline assumes that all policies in place in the current year will continue regardless of legally scheduled expirations or phase-outs. Specifically, the Senate budget plan shows a total $2 trillion deficit increase based on the “current policy baseline” assumption that the $3.3 trillion cost of the expiring tax cuts is already reflected in the baseline, which it is not. The actual deficit increase of the Senate plan is $5.3 trillion, not including increased interest on the debt.

The current policy baseline only makes sense from the perspective of the taxpayer, who sees no changes in taxes if the tax cut is extended and a tax increase if the tax cut is allowed to expire. If policymakers want to avoid imposing tax increases on people in the form of expiring tax cuts, then they should only pass tax cuts that are fully paid for on a permanent basis.

Unexpired or Back from the Dead

The “budget resolution” sets the parameters for how much reconciliation legislation can increase or decrease the deficit, and by law, must cover a budget window of at least five years, the upcoming year plus four additional years. In recent years, Congress has adopted as standard practice the use of a 10-year budget window. Further, in order for the budget resolution to trigger the filibuster proof reconciliation bill process, the resolution and subsequent “reconciliation” legislation are not allowed to increase the deficit outside the 10-year window. As a result, this creates incentives to arbitrarily sunset legislation in the middle of the 10-year time frame so that the 10-year cost is technically “reduced” – although the expectation is that Congress will later vote to extend the policy for the remainder of the 10-year period if not beyond (see current services versus current law baseline).

Both parties have heavily used this gimmick in recent years and OBBBA is no exception. The largest deficit increasing element of the House budget plan, at a cost of $3.8 trillion, is the extension of the expiring 2017 tax cuts. These tax cuts were originally set to expire at the end of 2025 to keep the deficit financed cost of the original Tax Cuts and Jobs Act below $1.5 trillion.

The House plan includes almost $300 billion in new tax cuts proposed by President Trump during the 2024 presidential campaign. These provisions include no tax on tips, no tax on overtime, additional elderly tax relief, and no tax on car loan interest. Each has a sunset date of December 31, 2028. In 2028, there will be tremendous pressure to extend these tax cuts and make them permanent.

No Go on PAYGO

Congress now makes a habit of simply ignoring the rules that are in place to control spending. Since 2010, Congress has lived under Statutory Pay-As-You-Go (S-PAYGO) rules. These S-PAYGO rules require Congress to offset the cost of any new tax reductions and mandatory spending expansions. Failure to pay for new policies that increase the deficit results in automatic spending cuts, known as sequestration.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) recently released an estimate of the required sequestration cuts triggered by the House reconciliation bill. CBO found that the enactment of the House Reconciliation bill would trigger automatic budget reductions of $230 billion per year to offset the 10-year cumulative debt increase of $2.3 trillion, not including the increase in interest on the debt. However, Congress and the president have canceled every sequestration cut since 2010. There is no reason to think that this year will be any different.

While ignoring S-PAYGO is alarming, CBO also found under S-PAYGO:

- Reductions in Medicare spending, which are limited to 4 percent, would be an estimated $45 billion for fiscal year 2026 – leaving $185 billion in reductions to be found in other programs ($260 billion in annual reductions less $45 billion in Medicare cuts equals $185 billion remaining).

- The S-PAYGO rules exempt many large spending categories from budget reductions, including those providing funding for Social Security and low-income programs,

- All of the remaining budgetary resources available for cuts total $120 billion, less than the $185 billion in remaining required cuts.

This means that the deficit increase in the OBBBA is so large that under existing S-PAYGO rules, $45 billion would be cut from Medicare and all remaining non-exempt spending would be eliminated and the plan would still increase the deficit by $65 billion per year and $650 billion over ten years.

Time for the Senate to Step Up

Now that the House has passed its reconciliation package the process moves to the Senate. However, the Senate’s reconciliation instructions include the “current policy baseline” gimmick that could lead to a ten-year increase in the debt of over $5 trillion. The Senate has the opportunity to take up the mantle of fiscal responsibility and ensure that any tax reductions and spending increases are fully paid for and do not increase the debt.

Continue Reading